Polyphony on the page: how authors portray music in their novels

Mrs Honeychurch disapproved of music, declaring that it always left her daughter peevish, unpractical and touchy,’ wrote EM Forster in A Room with a View (1908). It’s a sentence so intriguingly specific as to perk up anyone’s musical antennae. If Mrs Honeychurch doesn’t tempt you to reach – mid-chapter – for a brooding C minor sonata, how about the hushed reverence that descends on Covent Garden as a white-haired Peter Pears takes his seat in the Royal Opera House during a touching scene in Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library (1988)? That one might well have given you the urge to listen to Britten’s opera Death in Venice.

I’m obsessed with these fleeting musical touches that hide in the inner voices of a novelist’s polyphony. And to give an example from a play, in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), Algernon Moncrieff correctly identifies the arrival of his Aunt Augusta from the jangle of his doorbell, proclaiming, ‘Only relatives, or creditors, ever ring in that Wagnerian manner.’ That springs to my mind every time someone mentions Parsifal!

Do these small truisms stand out only to those who already have an emotional bond with musical life? I certainly feel that when a novel includes music so insightfully (or wittily), it increases my sense of connection with the characters through a shared sensibility. There are countless examples of musical references that have spoken directly to me throughout my life, and I am happy to admit that great storytelling has often introduced me to new repertoire and sparked fresh dimensions to my listening too.

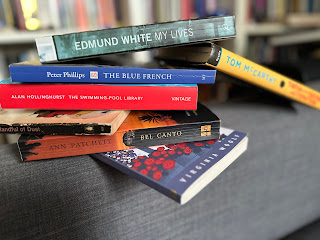

If, like me, you were fortunate enough to be bored during childhood summer holidays, you too might have discovered that long, listless afternoons were best countered with a book. I started with Tintin during that long, dry summer of 1984, and within several years progressed through all of my parents’ old paperbacks: EF Benson’s Mapp and Lucia, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, Forster’s Maurice … some I understood, some I didn’t. In the long impatient August before university, I found a love for WH Auden, Christopher Isherwood and Jack Kerouac, to the point that I romanticised wanderlust and began to feel that I too might sit on a dusty rucksack awaiting a Greyhound bus, smoking nonchalantly and penning the first line of a novel at once erudite and pregnant with meaning. However, books with musical references soon became my overwhelming favourites: The Nine Tailors (1934, by Dorothy L Sayers) with its bell-ringing methods, The Fish Can Sing (1957, by Halldór Laxnes) with its Icelandic song, An Equal Music (1999, by Vikram Seth) with its references to Bach’s Art of Fugue and, of course, there’s Appassionata (1996, by Jilly Cooper), which is set entirely in the world of classical music. Thankfully, my own attempted tale of a chubby countertenor’s journey to self-acceptance, and ultimately a place in a top vocal ensemble, never made it past the first draft; but I have maintained a lifelong devotion to summer reading and still reserve special admiration for books that include music, preferably early music.

[...]

To read the full text of this feature please visit Gramophone.co.uk (July 2025)

Comments

Post a Comment