Search This Blog

Early music and more by Edward Breen

Where possible, review entries are linked to their original publication.

Posts

Showing posts from May, 2011

Philipp Schoendorff: The Complete Works

- Get link

- Other Apps

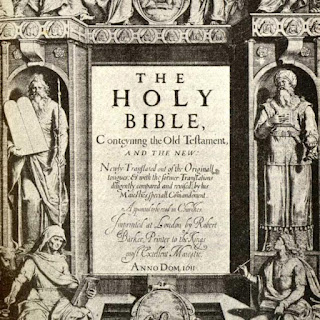

Celebrating the King James Bible at 400

- Get link

- Other Apps

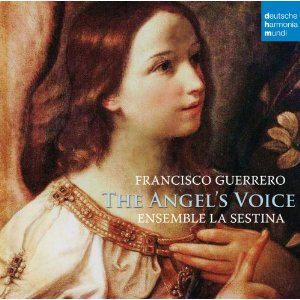

Francisco Guerrero: The Angel's Voice

- Get link

- Other Apps